|

Part

Two: The Carolina Club Orchestra, and Specht’s School for Jazz

Musicians

Having

enjoyed a successful visit to England with his band in 1923, Specht

returned to New York and continued to build up his orchestra empire.

By 1924 he had a fairly large roster of bands under his management and, as well as playing in America with

his own orchestra, he had booked bands to England, Europe and even

Australia. His own orchestra moved to the newly-opened Hotel Alamac,

where it played in the Congo Room and also broadcast over Radio

Station WHN. Sometime

about June 1924 Work Permits were requested from the Ministry of

Labour for Specht and the members of the Carolina Club Orchestra, a

college band from the University of North Carolina led by James Harold

(“Hal”) Kemp. Apparently without waiting to see if permits had

been granted, Specht and the band boarded the “Berengaria” and

sailed for England. Halfway across the Atlantic he received a cable

which stated “Regret Permits refused”; no reason was given. In

view of his concern at rumours which reached him before he left

England the previous year, it seems a little strange he did not wait

to ensure all permits were in place before sailing. (It

is likely the rumours emanated from Specht’s statement that he would

be sending over a further sixty musicians, in addition to the Frisco

Syncopators and the Criterion Orchestra.) On

arrival at Southampton on 18th July, 1924, Specht and the band were

refused admission to England, and were not allowed to disembark from

the ship. According to the Passenger List (BT26/777) the members of the band (plus Specht) were:

There

were clearly eleven men in the band, although not all of them may have

been present on the recordings made for Columbia Given

the situation he found himself in, it was fortunate for Specht that

the other passengers included a delegation of high-ranking lawyers,

who were visiting England to attend the Wembley Exhibition and other

events. The band had played for this delegation and other passengers

during the voyage. One member of this party was US Secretary of State,

Charles Hughes. Specht sought out Hughes and complained bitterly about

the treatment he was receiving, asking Hughes to fly and intercede on

his behalf Hughes

cabled New York and the American Embassy in London, and diplomatic

pressure was brought to bear on the British Government. In addition

the Buescher Instrument Company and the Columbia Graphophone Co. in

America both sent letters of protest to Washington, no doubt at

Specht’s request. Before

sailing, Specht had cabled Frank Guarente, who had by now left

Specht’s own band and was working in Europe. He asked Guarente to

meet him in London, not to play but to assist with administrative

matters. Guarente duly arrived at Folkestone on the South Coast, and

(according to Specht) was refused admission, locked up overnight

without food or drink, not allowed to get in touch with Specht, and

sent back across the English Channel on the first boat the next day. Variety

for

July 16th 1924 had earned a full-page advert for the Specht

organisation, including a note to the effect that Specht was coming to

England. His main purpose in coming was to sign a contract with the

Cunard Steamship Company, under which he would supply American bands

for all the liners in their fleet, which amounted to between forty and

fifty boats. The advert also earned details of the bands under his

management, which included Robert Bennett’s Frisco Syncopators,

Hughie Barrett, Ted Weems, the Lido Venice Dance Orchestra, the

Romancers and the Georgians. Since

the last two were actually “bands within a band” from Specht’s

own orchestra at the Hotel Alamac, it can be seen that this advert was

not entirely accurate! Another

section of this advert, referred to the Carolina Club Orchestra’s

visit, and stated this was 7or

the purpose of headlining the English music kills and to play at

British cafes at the Hotel Claridge in Paris and at the Winter Garden in

Berlin”. Given that

applicants for Work Permits

normally had to be specific

about where they were to be employed, and who would be employing them,

this may be why Permits were not granted in this case. Despite

having gained access to England, Specht was still nursing a grievance.

In early August he announced his intention to form a separate

Musicians Union, for the specific purpose of admitting bands under his

management into England. The reaction to this news from the

“genuine” Union was unfavourable, to say the least. This

suggestion of a “rival” Union was apparently part of a proposed

agreement he attempted to enter into with Jack Hylton regarding the

booking of bands. Under such an agreement, Hylton would be his agent

for American bands coming here, while Specht would act as agent in

America for bands which Hylton sent there. Jack Hylton decided not to

entertain this proposal,

not least because it would have required payment of 50%

of his earnings from all sources

over to Specht! Apart from being a somewhat dubious proposition, this

scheme seems to have totally ignored the ongoing policy of the AFM,

namely the refusal to permit any English band to work in America. This

rejection of his proposal incensed Specht still further and, as will

be seen, he repeatedly attacked Hylton in the musical press over the

next ten years. “Dear

Ol’

Lunnon” likes Yankee jazz so

well that a college of

syncopation, sponsored by Paul

Specht,

exclusive

Columbia artist, noted dance orchestra king and radio artist, of

New York has

just

been established in

the English metropolis

for the purpose of

instructing British musicians in

the

gentle art of

American

“danceopation" “,

according to word just received here.

The

new school is located at Grafton House, Golden Square, WI, London and

is under the

management

of

J.

Fenston, Ernest Collins and H. Lewis. It is known as Paul Specht 's

Institute of

Rhythmic

Symphonic Syncopation

and the instructors are all

American musicians. Three of

these

teachers,

Harl Smith, Everitt Davidson and William Haid

all of

New York,

recently sailed

for England. The

three American musicians listed above were all members of the Lido

Venice Dance Orchestra which did come to Europe in October 1924; their

activities in England will be covered later. Suffice it to say that

since the band was working in Europe at this time, if would have been

difficult if not impossible for these “teachers” to play there and

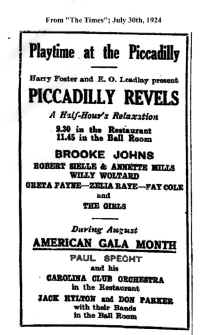

also teach in England. Work

Permits for the Carolina Club Orchestra had only been granted for a

period up to August 16th.

Somehow Specht managed

to get these extended for a further few days (duly reported in the Times

for August 15th) and the band finished playing at the Piccadilly Hotel on

August 21st. Two days later Specht and the band were aboard the

“Berengaria” again on their way back to America. According

to Specht, they were "smuggled on board ship and did not appear on the Passenger List”. (New York Times; September 6th, 1924).

On this return voyage the “Berengaria” was carrying the Prince of

Wales, no less, who was setting out on a Royal visit to America and

Canada The Prince had been to the Piccadilly Hotel several times

during the Carolina Club Band’s stay there, and was much impressed

with their playing. Specht maintained they had been smuggled on board

as a surprise for the Prince. However, the Passenger List (BT27/ 1066)

for this trip clearly shows the members of the band listed, along with

Specht - but

all travelling Third Class, and not Second Class as was normal with

musicians.

Notwithstanding Specht’s claims, I think it more likely that when

the Work Permits finally expired, they were ordered to leave the

country by the first available boat or be deported. Specht’s

problems were by no means over. About one day into the voyage, it was

announced that in view of the Prince of Wales’ great enthusiasm for

the music of the Carolina Club outfit, that band would play for the

Prince in the ship’s ballroom each night. The resident ship’s

orchestra were less than amused at this, threatened to take strike

action, and to call on the Seamen's Union to strike in sympathy. Again

according to Specht, the ship’s orchestra also threw over the

ship’s side all the Carolina Club’s band parts! (Reported in New

York Times,

September 6th, 1924). All

this was obviously very embarrassing for the Cunard Company with the

Prince of Wales on board, and there were frantic negotiations to try

and resolve matters. Specht insisted he had a contract to supply

orchestras for the Cunard boats, which was denied by the company’s

New York office. Finally it was agreed that the Carolina Club Band

would play for about two hours each night (presumably with or without

arrangements...). Regarding the Cunard contract, the New York Times for September 12th, 1924 carried a brief item to the effect that “arrangements have been made by the Cunard line with Paul Specht, orchestra leader, to place an orchestra on one of its largest ships. The ship had not yet been designated and whether Specht orchestras would be placed on all of the Cunard steamships would depend on the result of the experiment.” Not quite what Specht had stated would happen! All

this activity was reported at length in Variety and to a lesser extent

in other musical papers of the lime. (Billboard seems to have made no

mention of these events, possibly because Specht was at the time suing

them for libellous reporting of another matter.) When

Specht arrived in New York he continued to complain at length about the

treatment he had received in England, and the scene was set for further

difficulties in the following two years. Before

we move onto the next instalment, it is necessary to point out two

things: 1)

Specht always maintained he should be free to bring American bands to

England, in view of the many English artists who were working in America

without hindrance. What he consistently failed to make clear was the

vast majority of those artists were variety turns, and in

several cases had emigrated there and were now American citizens. Even

if they had not taken up citizenship, they had at least become members

of the AFM or a theatrical union. 2) As stated elsewhere, no English dance band was allowed to work in America during the Twenties, not even to appear as a stage act, because of the unrelenting opposition of the American federation of Musicians. click

here for: Part

Three: The lido Venice and Canadian Club Orchestras, and the Kit Cat

Club. Author:

JOE MOORE |